Reduce Parenting Frustration with a Mindset Shift to Objective Curiosity

Discover how a Designer’s Mindset can help you respond more calmly and effectively to everyday family challenges.

“She’s just lazy.”

“They’re doing this for attention.”

“This is a typical middle child behaviour.”

How often do you catch yourself making quick judgments about why your child is acting out based on what’s immediately visible or familiar? We’ve all been there. While most of us try to understand the reasons behind the challenges presented to us, we often do not go beyond turning what our judgments into questions: “Why is she so lazy with her homework lately? Is she doing this for attention?” While these thoughts are a start to digging deeper, they often stem from a position where you might be looking to ‘fix the person and their problematic behaviour’.

But here’s the thing. Our behaviours follow our thoughts. When our thoughts are built on assumptions and biased judgements, we risk reacting in ways that are not helpful, and might even escalate the situation.

A better approach is to view challenges with objective curiosity. Most parents are consciously trying to get more curious, but they might not be doing it objectively. That’s why, as a parent, one of the smartest things you can do when you are confronted with challenges at home, is to pause and say: “I see this is happening. I don’t know… what, why, how… yet. What can I do to find out.” It’s a small shift in your internal narrative that opens the door to objective curiosity.

Welcome to the first in our Designer’s Mindset Series where we explore the mindset shifts designers use to solve complex problems at work, and how these same shifts can transform everyday challenges at home.

Designer’s Mindset: Embrace ‘I Don’t Know’ to be Objectively Curious

In human-centered design, we start with the Discovery phase—and embracing “I don’t know” is critical, because if we don’t we’d simply be validating what we already know, which clearly defeats the purpose of discovery. For some, embracing ‘I don’t know’ requires active practice because this common phrase often goes against how our brains and society have conditioned us to respond.

Why ‘I Don’t Know’ Feels Harder Than It Should

1. We’ve been conditioned to equate certainty with competence.

We’ve been conditioned that leaders or people in authority, should have the answers. Admitting uncertainty can feel like a weakness, especially in front of children who look to us for guidance. As our children gain independence and their world expands beyond our visibility, the unconscious mindset of “I know better than you” that we carry with us, puts a barrier in the relationship, because we are not them, how can we know better?

2. Our brains are wired for efficiency.

Dr. Lisa Feldman Barrett, a leading neuroscientist, explains that the brain acts as a prediction machine, filling in gaps using past experiences to conserve energy. This is why we default to assumptions to help us survive the day.

3. Confirmation bias rewards us for feeling right, not being right.

Confirmation bias makes us notice what we expect, not necessarily what’s true. At home, where patterns are familiar, it’s easy to reinforce the same story. If you believe your child is defiant, your brain will spotlight behaviours that confirm it and filter out the rest. The need to feel right is deeply human, this makes us feel competent and in control.

Many designers tend to be curious.

But being objectively curious at home,

requires a conscious mindset shift,

just like everyone else.

Designers are trained to suspend judgment, stay curious, and assume we’re missing something, because we usually are. As a designer at work, being objective is often not difficult because we rarely work on projects that are deeply personal. Even for projects that are relevant to us, we’d belong to a group of collective and not singled-out.

Another reason I can think of is that the design process has ‘objectivity’ built into it. We have an array of tools to help us challenge assumptions and gather insights to help us see differently. All these contribute to building an environment that helps us to be objective whenever it is needed. For example, if we want our collaborators to understand what a specific user is going through, we present our research findings into a user journey map where it identifies the person’s key thoughts, actions, pain points, delights, etc. This ensures that we are all looking at the same view, leaving less chance for personal interpretations. Having a visual tool as such, helps drive objective discussions, clarify misunderstandings and move forward.

At home, where it’s personal and where emotions run high, being objective requires work. Personally, I didn’t apply what I knew until life nudged me to seek out better ways. It took conscious effort and practice to apply design skills at home. Whenever I am stressed, my default behaviour still takes over, but the difference now is that I have greater awareness, and is able to course-correct when needed.

For those who actively practice objective curiosity at work, you might be able to make the shift simply by reminding yourself to make the shift in your family interactions. And whenever you catch yourself assuming or not being objectively curious, you’ll develop your own ‘I don’t know’ narratives that helps you get back on track.

But if the thought of embracing ‘I Don’t Know’ sounds confusing or new to you, or if you are curious, but unsure if you’re being objective, I’ve developed the ABC tool below to help you start shifting your thoughts.

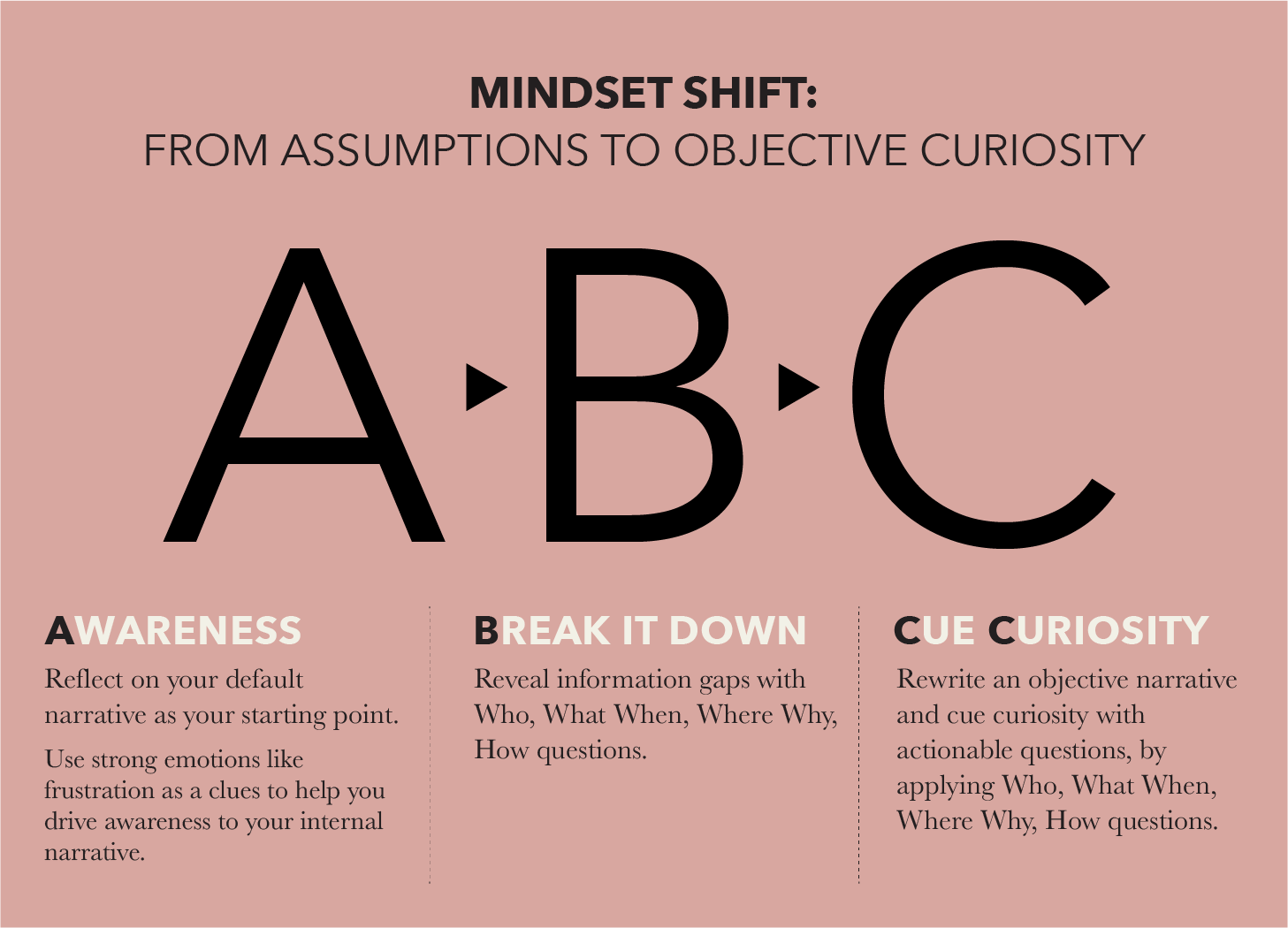

The ABC tool: Shift from Assumptions to Objective Curiosity

This tool is specifically designed to help you reveal gaps in your narrative, focus on facts, and remind yourself there’s always more to discover, and stay curious.

Important thing to note is that the goal of this tool is not meant to solve the problem that you have identified in your thoughts. The goal is to shift your narrative and eventually your response to similar or related situations.

A more detailed explanation on each step will be available in the coming days.

While it’s impossible to know all the why-what- how, to be a great parent across the multiple challenges we face at home. But what we can all do is design an approach that could build stronger relationships with our family by:

Modeling curiosity

Taking an active role in embracing change

Staying open, willingness to be wrong

Responding with empathy

The more certain we feel,

the less likely we are to discover what’s actually true.

Every “I don’t know” can be a door to better understanding, and every pause to stay curious can communicate “I love you enough to learn more about you” more than any words ever can.

I’d love to hear your thoughts, and your experience with this tool, so we can co-create better solutions to help us all be more connected at home. Please reach out.

Note: The insights and tools shared here are grounded in design thinking and psychological research. They are not a substitute for professional advice. If you find persistent, distressing patterns, or reactions like physical escalation, consider seeking support from a therapist or counsellor.