Breaking Down Ambiguity in Modern Families

Why our brains crave certainty, how it shapes our life at home, and what experts say we can do about it.

In an earlier post, we heard from parents and their challenges at home that revealed a common underlying thread. That is our struggle dealing with ambiguity. It’s the unsettling feeling of not knowing what’s right, what will work, or how today’s decision at home will impact tomorrow.

Here, we break it down to understand the science behind it.

Why Do We Struggle with Ambiguity?

Our brains interpret ‘not knowing’ as a threat, which triggers fear. So when parenting feels ambiguous, our brain is doing its job to avoid danger.

From our conversations with parents, ambiguity shows up in many ways:

Ambiguity of time

“If I don’t push him now, will we regret it later?”Ambiguity of an on-going experiment

“What works with one child, completely fails with another.”Ambiguity of modern safety

“I don’t want to keep fighting about screens, but I’m scared of what happens if I don’t.”

Parenting today isn’t just hard, it’s deeply ambiguous.

What Happens When We Sense Ambiguity?

Our brains switch to high alert. Cortisol rises, heart rate picks up and our fight or flight system is activated. We feel like we are losing control, so our brain scrambles to regain it.

Neuroscientists describe our brains as prediction machines. Its main job is to reduce uncertainty by making predictions based on available data. But at home, (unlike at work where we have metrics and reports) we rarely have enough data to be certain.

So the brain quickly patches the gaps with:

Assumptions: Filling the gaps in our stories.

Child avoids homework. He’s lazy.Biases: Mental shortcuts shaped by past experience.

He’s always on his phone. He is definitely addicted.Shortcuts: Quick actions to restore a sense of control.

Strictly enforcing room clean-up not because it’s needed, but because order soothes us.

Once the loop is closed, our brain relaxes, even if the conclusion isn’t based on facts. Any reason feels better than no reason, and any action feels safer than sitting in “I don’t know”.

When ‘What’s Natural’ Works Against Us

Our brain hasn’t evolved as fast as our society. Instincts that once kept us alive in the wilderness can harm relationships today. Left unchecked, they can lead to:

Parents pushing harder than needed, soothing their own anxiety rather than meeting the child’s needs.

Children feel judged, misunderstood, or ‘not good enough’.

Families get stuck in repeated conflicts, choosing certainty over curiosity.

Habits of control reinforced, making ambiguity even harder to tolerate.

Imagine driving your family though heavy fog. You wouldn’t shut everyone out and insist you know the way just because you’ve driven that road before. Of course, you’d ask for extra eyes on the road. But at home, many of us do.

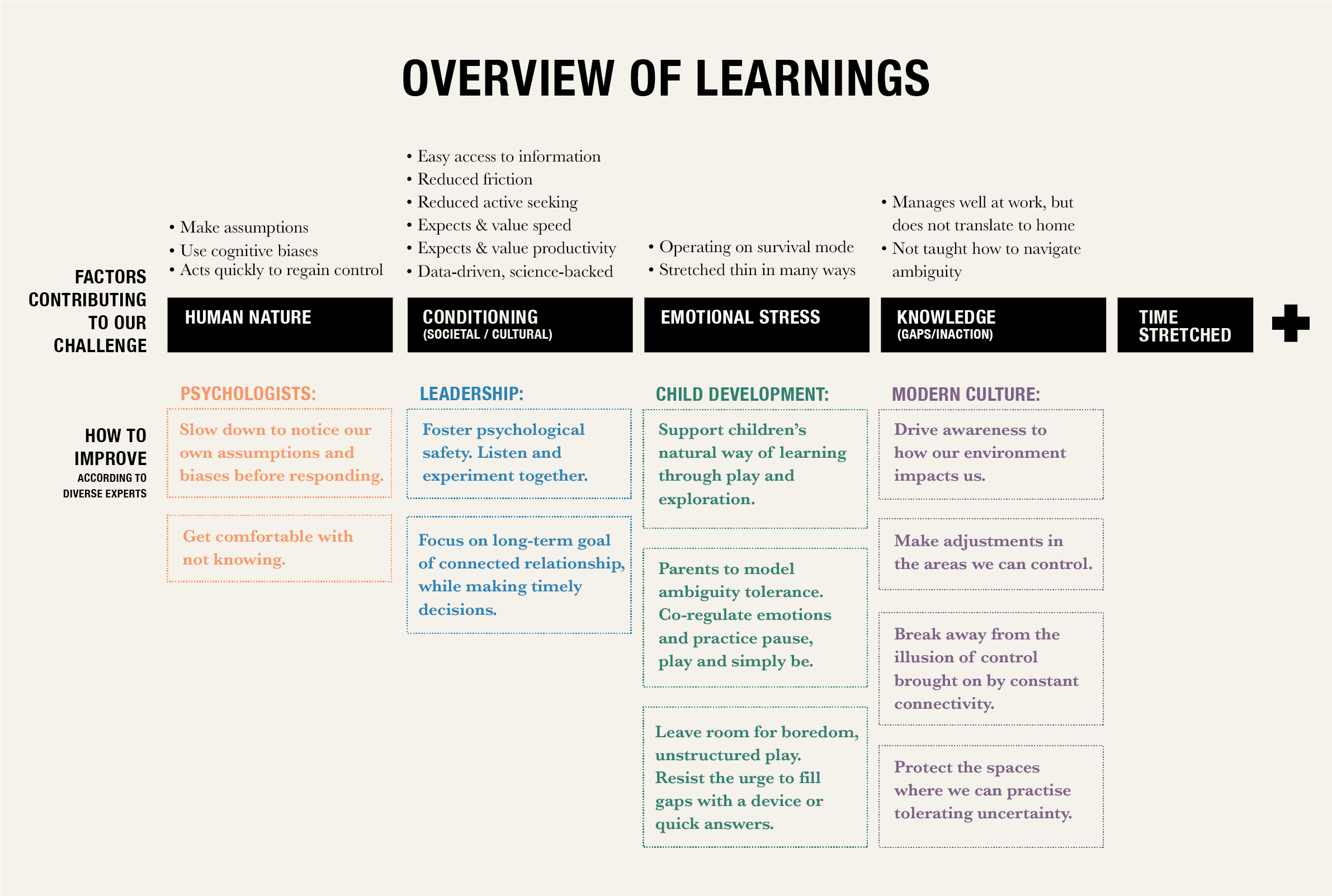

What Experts Suggest Will Help

[ Psychology ]

Researchers agree that the way forward is to train our brains to tolerate ambiguity. Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow reminds us that our brains default to fast, intuitive decisions. When stakes are high, shifting to slower, more deliberate thinking helps us catch biases before they drive our choices.

In family life, the stakes are high because we’re shaping the relationships with people who matter most. Slowing down gives us space to pause before reacting, notice our own assumptions, and respond to our family with curiosity rather than judgement.

[ Leadership ]

Leaders who thrive in uncertainty do not pretend to have all the answers. They balance clarity with flexibility, foster psychological safety, and encourage experimentation.

Robert Iger’s The Ride of a Lifetime shares how he navigated ambiguity at Disney by making timely decisions while keeping long-term vision in focus. Dr. Debbie Sutherland’s The Business of Ambiguity, highlights that effective leaders reflect on their assumptions, invite diverse perspectives and use sense-making practices to adapt as new information emerges.

At home, parents don’t need to have all the answers either. If we keep our long-term vision of building connected relationships in focus, we can make better day-to-day decisions that are more cohesive. We can also create psychological safety by listening openly, letting everyone express their fears and ideas and encouraging small experiments rather than pushing for perfect outcomes.

[ Child Development ]

Dr Ross Greene’s The Explosive Child reminds us that ‘kids do well if they can’, and their resistance is often a call for support. Dr Dan Siegel’s The Whole-Brain Child highlights the importance of co-regulation in building emotional tolerance.

Dr Alison Gopnik’s The Gardener and the Carpenter reframes parenting as creating conditions for exploration, instead of enforcing outcomes. Children naturally learn resilience, creativity and adaptability through play, observation, and experimentation.

Jonathan Haidt, in The Anxious Generation, warns that children today are growing up in environments where unstructured play and ambiguity are being eroded by constant digital connection. Instead of building resilience through trial and error, kids often turn to devices that offer instant distraction and certainty.

As parents, we need to model ambiguity tolerance ourselves to better guide our kids. That might mean leaving time for boredom, allowing unstructured play, or resisting the urge to fill every gap with a device or quick answers. And it’s not just for kids, we also need to pause, play and simply be, so we don’t send the message that only about productivity and control, something many of us are guilty of.

[ Modern Environment & Culture ]

Our world is increasingly designed to remove uncertainty for us. GPS, live feeds, instant notification, and even algorithm-driven feeds give us answers before we even have to ask. All of these leave little room for the unexpected.

Years ago, Sherry Turkle in Alone Together, warned how constant connectivity creates an illusion of control but erodes human connection. Today, with even more advanced technology, that illusion is stronger than ever, and impact is also bigger than ever.

Layer on top of the culture of speed and productivity. Many parents are operating in survival mode, constantly juggling work, kids, home, and their own sanity. In the rush, pausing to sit with uncertainty feels like a cruel joke. Add parental guilt to the mix, it becomes insanity.

So, while our brains are naturally wired to dislike ambiguity, modern culture can makes it even harder to practise. The good news is that awareness gives us choice. By noticing how our environment shapes us, we can start to tweak the spaces we can control (like, our home environment) to steer ourselves and our kids in a healthier direction.

Key Takeaways:

Our brains are wired to hate ambiguity, so we rush to close gaps with assumptions, biases and shortcuts. This calms us in the moment, but can harm our connection at home.

Psychology teaches us to slow down to notice our assumptions, and use our logical brain to make decisions.

Leadership reminds us to keep long-term vision in focus, create psychological safety, reflect on ourselves, and encourage experiments.

Child development shows that kids often struggle due to skill gaps. They build resilience through play, exploration, and co-regulation with adults, not from digital connection. Their natural curiosity and play are strengths to be nurtured, not suppressed. Parents and children can learn together the skills together, and from one another.

Modern culture pulls us away from ambiguity tolerance. But awareness gives us a choice to shape our environment to help us better manage it.

This wraps up our exploration of ambiguity through multiple perspectives. Not conclusive, but that’s ok. What we’ve gathered is enough to give us clues for moving forward as we think about how to design our family culture.

Next, we’ll start connecting our learnings to action, so we can shape practical ways to navigate ambiguity together.

Related posts

Introduction: Human-centered Design for Families, Why it matters at home

Methods to navigate ambiguity at home: 5W1H, Affinity Clustering, How Might We